Mário Teixeira Reis Neto, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4429-8457; Universidade Fumec, Brasil. E-mail: reisnetomario@gmail.com

Ana Lucrécia Fonte-Bôa, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7009-1188; Universidade Fumec, Brasil, E-mail: alfonteboa@gmail.com

Carlos Alberto Gonçalves, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1222-141X; Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brasil. E-mail: carlos11ag@gmail.com

Danilo de Melo Costa, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3001-0352; Universidade Fumec, Brasil / SKEMA Business School, Brasil. E-mail: danilomct@gmail.com

Abstract

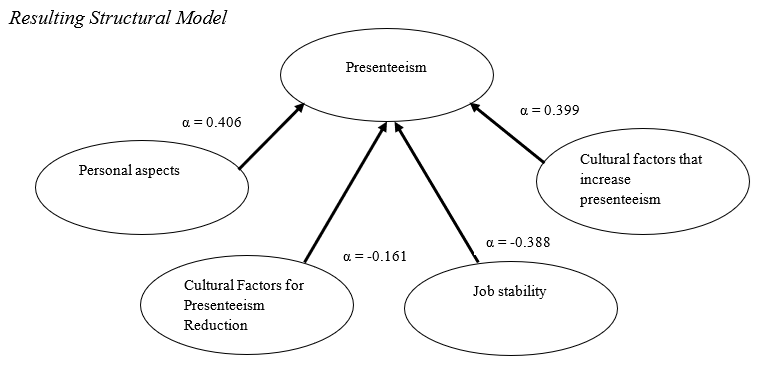

Presenteeism is a productivity-limiting event., identify and measure the factors that influence it and then to propose a structural model of influences on presenteeism, according to the perceptions of employees in companies in the electricity sector is the objective of this study. This is a descriptive, conclusive research, with a qualitative and quantitative approach. From 25 semi-structured interviews, a data collection instrument was generated which was applied to 1.778 employees, in 3 electric energy concessionaires[1] in Brazil. Data analysis was performed using Structural Equation Modeling, PLS (Partial Least Squares) approach and CB-SEM (Covariance-based Structural Equation Modeling Techniques). The constructs that most influenced presenteeism were Personal Aspects (α = 0.406), Cultural Factors for Increasing presenteeism (α = 0.399) and the perception of Job Stability (α = 0.388). The results pointed out possible actions in People Management cases of presenteeism. This article provides insights for replicating this research in other segments or regions.

Keywords: Presenteeism; People management; Electric sector.

Resumo

O presenteísmo é um evento limitador da produtividade. A identificação e mensuração dos fatores que influenciam o presenteísmo, com elaboração de um modelo estrutural, segundo as percepções dos empregados em empresas do setor de energia elétrica é o objetivo deste estudo. Trata-se de uma pesquisa descritiva, conclusiva, de abordagem qualitativa e quantitativa. A partir de 25 entrevistas semi-estruturadas foi gerado um instrumento de coleta de dados que foi aplicado em 1.778 pessoas, em 3 concessionárias de energia elétrica no Brasil. A análise dos dados foi feita utilizando-se a Modelagem de Equações Estruturais, abordagem PLS (Partial Least Squares) e estrutura de covariância CB-SEM (Covariance-based Structural Equation Modeling Techniques). Os construtos que mais influenciam o presenteísmo foram os aspectos pessoais (α = 0.406), os fatores culturais de aumento do presenteísmo (α = 0.399) e a percepção de estabilidade no emprego (α = 0.388). Os resultados apontaram possíveis ações na Gestão de Pessoas sobre as ocorrências de presenteísmo. Este artigo fornece elementos para a replicação desta pesquisa em outros segmentos ou regiões.

Palavras-chave: Presenteísmo; Gestão de Pessoas; Setor elétrico.

Citation: Neto, M. T. R., Fonte-Bôa, A. L., Gonçalves, C. A., & Costa, D. M. (2024). Presenteísmo: um modelo estrutural. Gestão & Regionalidade. v.X, e2023XXX. https//doi.org/10.13037/gr.volX.e2023XXX

Presenteeism was a term coined by a psychologist and organizational management expert named Cary Cooper (Flores-Sandí, 2006). The term was used to describe the phenomenon of people attending work while ill, primarily out of fear of losing their jobs, resulting in a loss of productivity. Presenteeism can be understood as the worker's presence in their workplace solely in body, with productivity impaired for various reasons (Aguiar & Burgardt, 2018). In summary, presenteeism is "absentee presence." The phenomenon or event of presenteeism may go unnoticed and is often not measured. Identifying it relies on the perception of those around the presentee. However, its effects are observed in the outcomes and productivity of the area, thus requiring management. Measuring the costs of presenteeism is a challenge in organizations, unlike absenteeism. Cancelliere et al. (2011) demonstrate the impact of health issues on work performance, suggesting that expenses related to presenteeism can be four times higher than those associated with absenteeism. Therefore, presenteeism can generate expenses for organizations because it is difficult to identify and address. Schultz and Edington (2007) linked presenteeism to health-related causes. For various reasons, individuals are willing to go to work even when they have health problems, but while at work, they do not perform at an optimal level.

According to Santi, Barbieri and Cheade (2018), presenteeism is also influenced by the perception of job stability. In this case, presenteeism occurs when the employee perceives job security, has no desire to leave the organization they work for, but has different interests from what is assigned or expected on a particular day or task. It is a voluntary decision supported by their own motivational factors.

Associated with the perception of stability is organizational culture. Organizational culture is comprised of three levels of knowledge: basic assumptions, beliefs considered acquired about the company and human nature; values, which are important principles, norms, and models; and artifacts, which are visible results of a company's actions and are supported by its values (Schein, 1990). People perceive what they do through their personal perceptions (Morgan, 1996). Therefore, every organization establishes a culture regarding how work is conducted, either facilitating or inhibiting presenteeism. Presenteeism, whether perceived individually or collectively, can indeed be an element of organizational culture. Haque, Fernando and Caputi (2019) suggest that the perceived human resource management policy directly influences presenteeism and the intention to leave the organization. Negative perceptions about the human resource management policy can increase presenteeism and also raise the intention to leave the organization. Presenteeism is characterized as a new challenge in contemporary management with an impact on various sectors of the economy, including the electrical sector. Since the year 2000. the costs of the electrical sector ceased to be shared and began to be managed and monitored in a differentiated manner, gradually increasing competitiveness and the demand for efficiency (Aneel, 2015). However, Fernandino and Oliveira (2010) had already highlighted the need for electric utility companies to invest in new management techniques, as well as in technology and innovation (both tools and processes). Technological changes are rapidly and disruptively advancing, altering the way we live, think, relate to one another, and generate, store, and consume energy. These changes require the electric sector to have employees who are truly present and engaged in their organizations.

The literature suggests that presenteeism is influenced by constructs related to personal factors, individual perception of job stability, and cultural factors within the organization. However, there is no indication of which constructs are prevalent, nor is there an indication of the prevalence of elements within each of these constructs. The influences of the various related variables require a differentiated approach to people management, in order to understand and address such occurrences. This is becoming increasingly necessary, as the demand for efficiency gains is a constant in the daily routines of organizations. Thus, the objective of this study is to propose a structural model based on the identification and measurement of factors influencing presenteeism, according to the perceptions of employees in companies within the electrical energy sector. It's worth noting that in Brazil, there are few scientific publications on presenteeism, and the term is unfamiliar to both employees and organizations. It has not yet been recognized within the managerial context, making its measurement, evaluation, and management challenging.

The theoretical framework presents presenteeism and the challenges of management, its relationship with health, job stability, trust relationships, and from a personal perspective.

Presenteeism can be understood as "being present in body but absent in mind," as the individual is physically at work but mentally or functionally absent, either partially or wholly (Aguiar & Burgardt, 2018). Presenteeism is a productivity-limiting event that impacts organizations and is undesirable. It can affect the quantity or volume of work delivered and the quality of work through errors, omissions, difficulties in concentration, among other factors.

Presenteeism can be understood as a competitive behavior when an individual aims to demonstrate unreal commitment, even in unfavorable physical and mental conditions. The insecurity stemming from a restricted job market or unemployment can be related to presenteeism, as the decision to remain at work is seen as a condition for job retention. (Flores-Sandí, 2006).

In the literature, it's possible to identify two different schools of thought regarding presenteeism, one originating in Europe and the other in the United States. In Europe, presenteeism is often seen as a result of job security concerns, therefore with a collective focus. In the United States, presenteeism is approached more from an individual perspective. In Brazil, presenteeism is frequently treated in a pejorative manner and is not often associated with health issues, which makes diagnosis and early treatment challenging, potentially leading to the worsening of situations. (Elkeles & Seligmann-Silva, 2010).

The surveys conducted by Aguiar and Burgardt (2018) identified a very limited number of scientific studies on presenteeism in the public service, highlighting the importance of further research in this area. The authors emphasize that the impact of presenteeism on productivity is equivalent to that of absenteeism. Both represent two sides of the same reality experienced in the world of work, as both are understood as forms of absence from work.

Expanding the perspective on presenteeism is important due to its impact on the lives of the individuals involved and on business outcomes. As a subtle event, presenteeism can be easily overlooked. Specifically in the field of Human Resource Management, the discussion about workforce productivity has shifted its focus from absenteeism to presenteeism due to the prevalence of various illnesses, working conditions, and employees who choose to work while being ill (Chapman, 2005; Halbesleben et al, 2014; Haque, 2018).

Dutra et al. (2018) explain the need for investments in the field of human resource management to motivate professionals, as demotivation resulting from the absence of training, recognition, clear job and salary policies, among other variables, can lead to high levels of demotivation and consequently presenteeism.

Haque, Fernando, and Caputi (2019), in their research conducted with workers in Australia, identified that effective human resource management can reduce employee turnover intentions and, more importantly, presenteeism. It is necessary to take a more direct approach with clear policies regarding this issue, which is the subject addressed in their research.

From this point onwards, the following sections provide a detailed exploration of the relationship between presenteeism and factors that can influence its occurrence.

Cooper (2011) categorizes the manifestations of presenteeism in organizations into four circumstances: Healthy and motivated workers who are fully present for work and the organization, and do not become ill; Workers who are present at work regularly, even when they are sick, resulting in reduced productivity; Healthy but dissatisfied workers with reduced productivity; Workers with some chronic (or severe) health problem related to work, resulting in reduced productivity.

Even if there are no clear physiological signs in an employee, a decrease in their productivity with below-normal quality of work is an indicator of presenteeism (Koopman et al., 2002). According to Schultz and Edington (2007), there is a relationship between an employee's health and their productivity at work as well.

Being at work is a decision made by the worker, which may be based on the need for survival but can also be influenced by personal factors and the family and social contexts. The interface between work and family has evolved in recent decades, highlighting the need for a balance between personal and professional life. Oliveira, Cavazotte, and Paciello (2013) state that conflicts can arise from both sides and impact job satisfaction and the desire to stay with the company, indirectly related to presenteeism.

Presenteeism can be caused by factors related to mental, physical, and emotional well-being, and it can be approached from epidemiological, qualitative, and economic perspectives (Aguiar & Burgardt, 2018). Issues related to alcoholism, smoking, substance abuse, excessive material consumption, obesity, accidents, and illnesses deserve attention when examining presenteeism because its manifestation is subtle and challenging to detect.

Presenteeism-disease is characterized by the employee's non-effective presence at work, which they impose upon themselves. Avoiding or reducing presenteeism-disease may involve addressing working conditions to promote the full exercise of functions, recognition and quality, autonomy in the workplace, and the absence of production pressure (Aronsson & Lindh, 2004). In the context of Biron et al.'s (2006) research, workers went to work 50% of the time when they were ill. The propensity for presenteeism was higher among workers who became ill more frequently.

Mental and physical health are interconnected with work and are essential for the optimal performance of employees. Stress, anxiety, or depression are factors that can have negative impacts on well-being and the completion of tasks, potentially leading to absenteeism, presenteeism, and, in some cases, employee separations (Biron et al. 2006). The relationship between an employee's health status and the occurrence of presenteeism has been evident in some research studies. Absences from work due to health reasons are protected by law, but the insistence on being present at work with compromised health suggests a concern about job security driven by some form of interest. Therefore, job stability is an issue worth exploring. Exploring presenteeism from the worker's perspective can be a way to understand the factors influencing it and, from there, identify actions to mitigate, reduce, or eliminate it.

Security is the second basic human need according to Maslow (1943). Stability is synonymous with firmness and solidity. Job stability is the right to remain employed, even against the employer's will (Fernandes, 2015), so it can be interpreted as a factor of security. The quality of work relationships and the length of time spent working in the same place are related to the emotional commitment of the worker to the job (Santi, Barbieri & Cheade, 2018). Better interpersonal relationships increase the likelihood of reducing sick leave days among employees.

The longer a career at the same workplace, the greater the job stability, leading to a stronger emotional commitment to the job. Stability can be a legal condition or a result of organizational culture. However, it can be assumed that the emotional relationships established in the workplace and with the job can influence commitment and presenteeism. Therefore, the trust established between colleagues and superiors can be considered a relevant factor in the occurrence of presenteeism.

Interpersonal relationships and power dynamics influence the decision to be at work and how to be at work. The way medical leaves are monitored and handled can also influence behavior at work. Companies that tightly control the granting of medical leaves may experience a higher incidence of presenteeism, which, in the long run, can translate into extended and lasting absenteeism, often driven by more serious illnesses. The correlation between presenteeism and absenteeism is not always identified or recognized as a direct relationship due to the subtlety of presenteeism occurrences. Absenteeism and presenteeism represent two sides of the same reality experienced in the world of work (Aguiar & Burgardt, 2018).

The strength of the psychological contract established between the employee and the organization is one aspect of the work relationship to be considered when identifying presenteeism. In addition to understanding what psychological contracts are and how they function, it's essential to comprehend the cultural context in which they occur, the place, and the time (Rios & Gondim, 2010).

The repression or censorship of absenteeism can be understood as a factor that generates presenteeism. Therefore, it can be inferred that building trust in the workplace can mitigate the occurrence of presenteeism and give absenteeism its proper credibility. Thus, both events can be influenced by personal factors.

This research can be characterized as descriptive, conclusive, and utilizing both qualitative and quantitative approaches.

The data collection instruments presented by Ferreira et al. (2010), the Work Limitations Questionnaire Reduced Form - WLQ-8. and the Stanford Presenteeism Scale - SPS-S-6 served as the foundation for the development of the interview script found in Appendix A. Twenty-five semi-structured interviews were conducted with employees of an electric utility company, following the script transcribed below. The interviews took place between September 1. 2016. and October 31. 2016.

Semi-Structured Research Interview Script:

• Does the company have any measures in place to prevent absences?

• How do managers react to absences? What about your colleagues?

• Do you perceive any relationship between absence and career development? Please explain.

• How would you evaluate the flexibility of negotiating absences and presences?

• Are you familiar with the Company's Attendance Manual?

• Are you familiar with the legislation regarding work absences?

• Is it possible to compare the company's policies and the current legislation? What is your assessment?

• Even though it's provided for in the company's rules or specific legislation, what are the effects of absenteeism on the company and the employee?

As planned in the semi-structured interviews, the topics were not addressed exactly in the transcribed order, and other questions emerged during the conversations. As the interviewees felt comfortable bringing up new issues and approaches to the topic, the conversation unfolded, allowing for an enriched discussion, which subsequently led to the research questionnaire. The interviews were recorded and later transcribed. Content analysis (Bardin, 2009) enabled the identification of the aspects most perceived by the interviewees regarding the topic and the development of an exclusive quantitative instrument to investigate the factors leading to presenteeism in organizations. Twenty-six presenteeism variables were identified, grouped according to the four constructs presented in Table 1:

Table 1

Model of the Instrument Resulting from Qualitative Work

|

Constructs |

Acronym |

Descricption |

|

Personal aspects (AP) |

AP1 |

People with health problems in the family produce less. |

|

AP2 |

People with pain and discomfort produce less. |

|

|

AP3 |

Weight gain contributes to delays in completing tasks. |

|

|

AP4 |

Financial problems lead to distraction or low productivity in my department. |

|

|

AP5 |

Lack of motivation or discouragement affects production in my department. |

|

|

AP6 |

Emotional and family issues reduce production in my department. |

|

|

AP7 |

People who are transferred to my department against their will feel out of place, demotivated, and produce less |

|

|

Cultural Factors for Reducing Presenteeism (FCR) |

FCR1 |

|

|

FCR2 |

In general, people in my department are concerned about developing what is requested of them. |

|

|

FCR3 |

Even with health problems, people continue to be present and perform their tasks. |

|

|

FCR4 |

It is the dominant culture in my department to work with determination, even with minor complaints, colds, or tolerable pains. |

|

|

FCR5 |

Some people work while ill out of fear of being laid off by the company. |

|

|

FCR6 |

People are able to concentrate on their work without distraction and disruptions during working hours. |

|

|

FCR7 |

In general, people in my department work the hours they are requested to. |

|

|

FCR8 |

In my department, those who finish their tasks first help their colleagues complete their work. |

|

|

Job Stability (EE) |

EE1 |

In general, people in my department start their tasks as soon as they arrive. |

|

EE2 |

In my department, people are late or absent because they know they will not be terminated by the company. |

|

|

EE3 |

Some people in my department frequently take time off to pay bills or for other purposes. |

|

|

EE4 |

The absence of an electronic time tracking system contributes to delays. |

|

|

EE5 |

Some spend more time than necessary in the break area or restroom facilities. |

|

|

Cultural Factors for Increasing Presenteeism (FCA) |

FCA1 |

I notice that some people access social media (WhatsApp, Facebook, etc.) and the internet (news and unrelated research) during working hours. |

|

FCA2 |

Regular work breaks, entertainment and relaxation sessions, snack times contribute to people getting distracted. |

|

|

FCA3 |

In my department, people often stop a task due to a lack of definition, guidance, or authorization. |

|

|

FCA4 |

I observe in my department that some activities are seen as a waste of time. |

|

|

FCA5 |

When a task is completed close to the end of the workday, another activity is only started in the next working period. |

With these elements, a data collection instrument was developed using a Likert-type scale of agreement ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree), with 7 variables for characterizing the interviewee and an additional 26 variables to investigate the subject of this study. They were divided into four first-order constructs (Personal Aspects, Cultural Factors for Reducing Presenteeism, Job Stability, and Cultural Factors for Increasing Presenteeism) and one second-order construct (Presenteeism).

Regarding the population and sample, employees from three electric utility companies located in Brazil, specifically in the Southeast region, were surveyed, promoting a business management analysis in a regional context to contribute to the advancement of companies in the region and potentially serve as a model for other regions. A total of 1.778 valid questionnaires were obtained, with 1.687 from the first company, 63 from the second company, and 28 from the third company. The surveyed companies had, respectively, 6.025. 227. and 96 employees. All employees were invited to respond to the questionnaire via their institutional email. The email explained the research's objectives and assured anonymity in the digital platform provided for responses. Participation in the survey was voluntary. Data collection took place from March to June 2017.

In the treatment of the collected data, the mean and standard deviation were used, along with the 95% confidence interval bootstrap percentile range, to present and compare the items of each construct (Efron & Tibshirani, 1993). Since the Likert-type agreement scale was set to range from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree), thus, negative mean values indicate that individuals tend to disagree, while positive values indicate that individuals tend to agree.

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was conducted using the Partial Least Squares (PLS) approach, which is based on the covariance-based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM) framework. The PLS method has been referred to as a gentle modeling technique with minimal demands concerning measurement scales, sample size, and residual distributions (Monecke & Leisch, 2012).

The Presenteeism construct is a second-order construct, meaning it was not directly formed by the items (questions) but by other latent variables (indicators). To handle this characteristic of the measurement structure, the "Two-Step" approach (Sanchez, 2013) was used. First, the scores of the first-order latent variables were computed using Factor Analysis with the method of principal components extraction and promax rotation (Mingoti, 2007).

To analyze the quality and validity of the first-order constructs, dimensionality, reliability, and convergent validity were assessed. Convergent validity was assessed using the criterion proposed by Fornell and Larcker (1981), which indicates convergent validity when the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is greater than 50% or 40% in the case of exploratory research. Cronbach's Alpha (CA) and Composite Reliability (CR) were used to measure reliability (Chin, 1998). According to Tenenhaus et al. (2005), CA and CR indicators should be greater than 0.70 to indicate construct reliability, with values above 0.60 also accepted in exploratory research. To verify the dimensionality of the constructs, the Acceleration Factor (AF) criterion (Raîche et al., 2013) was used, which determines the number of dimensions based on the number of factors where a sharp drop in eigenvalues occurs on the screeplot graph. The adequacy of the sample for using factor analysis was measured through the KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) indicator, which indicates the proportion of variance in the data that can be considered common to all variables. It is a measure that ranges from 0 to 1. with values closer to 1 indicating a more appropriate sample for factor analysis. It is suitable to apply Exploratory Factor Analysis to the set of variables when KMO is greater than 0.50.

While the first-order constructs are reflective, the second-order constructs are formative. In this way, the first-order constructs are the causes of their respective second-order constructs, while the items (questions) are the reflections of their respective first-order constructs. The validation of a formative structural model requires different approaches than the reflective model. Conventional validation and reliability assessment of constructs should not be applied to formative models (Bollen, 1989). Therefore, to assess the formative model, it was verified whether the weights were significant or greater than 0.20 and whether the factor loadings were greater than 0.60. If there are non-significant weights and low factor loadings, there is no empirical support to keep the indicator in the model (Cenfetelli & Bassellier, 2009). Additionally, Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) were evaluated to check for multicollinearity issues, with VIFs greater than 5 indicating a problem. Subsequently, correlations between the second-order constructs were calculated.

To compare the indicators with nominal qualitative variables, the Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used (Hollander & Wolfe, 1999). Spearman's Correlation was used to compare the indices with ordinal qualitative variables (Hollander & Wolfe, 1999). The model was adjusted again for the two groups (Company 1 and Company 2/Company 3), and the models were compared using multigroup comparisons. According to Hair et al. (2009), a multigroup analysis can be conducted in the context of different groups to explore potential changes in the measurement or relationships of constructs, allowing you to assess whether the theoretical model appears stable or not across the groups. The software used for the analyses was R (versão 3.3.1).

The presentation of the results characterizes the survey respondents, demonstrates the statistical treatments, and the exploratory factor analysis that forms the basis for proposing a structural model.

The questionnaire included seven demographic questions. Table 2 contains the descriptive analysis of the demographic variables of the respondents.

Table 2

Descriptive analysis of demographic variables

Escolaridade

Plano funcional

Área de Atuação

|

Characteristics |

Nº |

% |

|

|

Company |

Company 1 |

1687 |

94.9% |

|

Company 2 |

63 |

3.5% |

|

|

Company 3 |

28 |

1.6% |

|

|

Gender |

Female |

392 |

22.0% |

|

Male |

1386 |

78.0% |

|

|

Age |

18 to 25 years |

51 |

2.9% |

|

26 to 30 years |

144 |

8.1% |

|

|

31 to 35 years |

275 |

15.5% |

|

|

36 to 40 years |

160 |

9.0% |

|

|

41 to 45 years |

428 |

24.1% |

|

|

46 to 50 years |

368 |

20.7% |

|

|

Over 50 years |

352 |

19.8% |

|

|

Time in the company |

less than 5 years |

326 |

18.6% |

|

6 to 10 years |

117 |

6.7% |

|

|

11 to 15 years |

203 |

11.6% |

|

|

16 to 20 years |

106 |

6.1% |

|

|

21 to 25 years |

104 |

5.9% |

|

|

Over 25 years |

894 |

51.1% |

|

| Elementary School |

14 |

0.8% |

|

|

High School |

503 |

28.3% |

|

|

Higher Education |

711 |

40.0% |

|

|

Postgraduate |

451 |

25.4% |

|

|

Master's Degree |

96 |

5.4% |

|

|

Ph.D. |

3 |

0.2% |

|

| Administrative |

245 |

13.8% |

|

|

Management |

62 |

3.5% |

|

|

Operational |

190 |

10.7% |

|

|

Technical |

876 |

49.3% |

|

|

University |

405 |

22.8% |

|

| Mixed: field/office |

489 |

27.5% |

|

|

Primarily field |

274 |

15.4% |

|

|

Primarily office |

1007 |

56.6% |

|

|

Primarily power plant |

8 |

0.4% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Based on the data, it can be highlighted that:

• 94.9% of the respondents were from Company 1.

• 78.0% of the respondents were male,

• 24.1% of the respondents were aged between 41 and 45 years, while only 2.9% were aged between 18 and 25 years.

• 51.1% of individuals had been with the company for more than 25 years, and 40.0% had a college education.

• 49.3% of the respondents had a technical job profile, while only 3.5% had a management job profile.

• 56.6% of individuals had an area of expertise primarily in the office, while only 0.4% had an area of expertise primarily in the power plant.

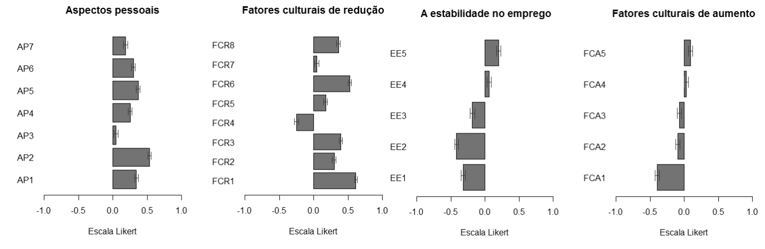

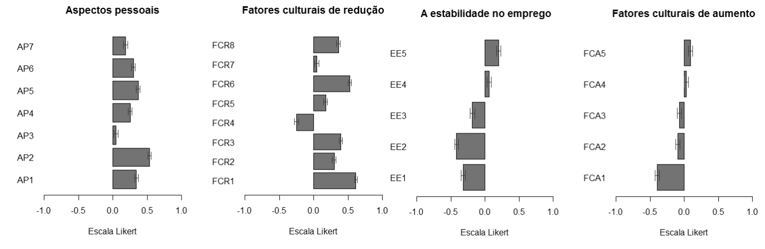

As the Likert scale ranged from 1 to 7, lower mean values indicate that individuals tend to disagree, while higher mean values indicate that individuals tend to agree. The mean, standard deviation, and bootstrap confidence interval were calculated for each item. The confidence interval is a tool that can be used to check if the difference between two groups is significant. If the intervals of the two groups do not overlap, there is evidence that the difference is significant. If the intervals overlap, there is no significant difference. Figure 1 illustrates the values found (Refer to Table 1 for the meaning of each abbreviation).

Figure 1

Means of the confidence intervals for the items of the Presenteeism constructs

The evaluation of the items in each construct allows for highlighting some relevant points and comparing differences between them. In Personal Aspects, it can be observed that, on average, there is agreement with all the items. Comparing the confidence intervals, it can be seen that item AP2 ("People with aches and discomfort produce little") had a significantly higher average than the others, while item AP3 ("Weight gain contributes to delays in completing tasks") had a significantly lower average than the others. It can be inferred that presenteeism was more related to a person's well-being than their physical condition.

Observing the construct Cultural Factors for Reducing Presenteeism, there is disagreement with item FCR4 ("Some people work when they're sick out of fear of being fired by the Company") and greater agreement with FCR1 ("In general, people in my department are concerned with completing their tasks as requested"). These items suggest that presence at work is perceived as effective, as sick individuals do not come to work, and those who do come to work complete their tasks.

In terms of Job Stability, there is no uniformity in the average tendencies, but less significant agreements are observed compared to disagreements. The highest average agreement occurs in item EE5 ("I notice that some people access social networks (WhatsApp, Facebook...) and the internet (news and non-work-related research) during working hours"), indicating a relatively new behavior, as technology has been revolutionizing the way people communicate, access information, build relationships, and, in general, live their lives, including the workplace.

The most significant disagreement is observed in item EE2 ("Some people in my department are frequently absent to pay bills or for other purposes"), confirming the digitalization of people's routines identified in the agreement with item EE5. In this item, a difference in the level of agreement was identified among items EE1 ("In my department, people are late or absent because they know they won't be fired from the company"), EE2 ("Some people in my department are frequently absent to pay bills or for other purposes"), EE3 ("The lack of an electronic check-in and check-out system contributes to delays"), and EE4 ("Some spend more time than necessary in the coffee break or in the restrooms") between Company 1 and Companies 2 and 3. In Company 1, the agreement was higher, which can be explained by the fact that it is a public-private company, hires through public competitions, and therefore generates a sense of pseudo-stability (there is no legal stability, but rather a cultural perception of it).

In the construct "Cultural factors increasing presenteeism", there was uniformity among the items, with average tendencies being close. The disagreement with item FCA1 ("Regular work breaks, entertainment and relaxation sessions, and lunch breaks contribute to people's dispersion") stands out for having a significantly lower average than the others. Disagreement with this item can be understood as a valuing of social relationships and non-work moments as contributions to work, rather than the other way around. Item FCA5 ("When a task is completed close to the end of the workday, another task is only started in the next work period") had a significantly higher average than the others, and this agreement can be understood as a common way of organizing work and can be perceived as positive.

The overlap of confidence intervals allows us to conclude that there is no significant difference in the perception of presenteeism among the researched companies. Differences in capital formation, employee hiring methods, and management do not significantly affect the perception of presenteeism in the surveyed electrical sector companies.

Through Exploratory Factor Analysis, it is possible to verify if there are any items (questions) that do not contribute to the formation of the indices. Hair et al. (2009) recommend that items with factor loadings less than 0.50 should be eliminated from the constructs, as they can contaminate and distort basic assumptions for the validity and quality of the indicators created to represent the research concept. In this research, some items with factor loadings less than 0.50 were identified and were therefore removed from the model, namely: item FCR4 from the construct Cultural factors for reducing and item FCA1 from the construct Cultural factors for increasing.

The verification of the dimensionality, reliability, and convergent validity of the constructs allows for an analysis of their quality and validity. It was found that all constructs exhibited convergent validity (AVE > 0.40), Cronbach's Alpha (AC) and Composite Reliability (CC) above 0.60. The fit of the Factor Analysis was adequate, with KMO values greater than or equal to 0.50. According to the Acceleration Factor criterion, all constructs were unidimensional, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3

Reliability, Convergent Validity and Dimensionality of Constructs

|

Constructs |

Itens |

AVE |

AC |

CC |

KMO |

Dim. |

|

|

Presenteeism |

Personal aspects |

7 |

0.493 |

0.817 |

0.821 |

0.824 |

1 |

|

Cultural Factors for Presenteeism Reduction |

7 |

0.474 |

0.809 |

0.811 |

0.848 |

1 |

|

|

Job Stability |

5 |

0.568 |

0.807 |

0.808 |

0.798 |

1 |

|

|

Cultural Factors for Presenteeism Increase |

4 |

0.490 |

0.649 |

0.721 |

0.701 |

1 |

|

The data presented in Table 4 suggest that there was a tendency for the sampled elements to agree with all the items of the Personal Aspects and Cultural Factors for Presenteeism Reduction indicators. On the other hand, there was a tendency to disagree with the indicators of Job Stability and Cultural Factors for Presenteeism Increase.

Table 4

Description of First-Order Indicators

|

Constructs |

Means |

D.P. |

I.C. - 95% |

1º Q |

2º Q |

3º Q |

|

Personal aspects |

0.299 |

0.425 |

[0.28; 0.32] |

0.028 |

0.34 |

0.613 |

|

Cultural Factors for Presenteeism Reduction |

0.352 |

0.379 |

[0.34; 0.37] |

0.104 |

0.394 |

0.635 |

|

Job stability and presenteeism |

-0.131 |

0.52 |

[-0.16; -0.11] |

-0.537 |

-0.134 |

0.265 |

|

Cultural factors that increase presenteeism |

-0.009 |

0.475 |

[-0.03; 0.01] |

-0.341 |

0.007 |

0.338 |

The indicators showed significant differences, with the indicator with the highest mean being Cultural factors that reduce presenteeism (0.352), and the indicator with the lowest mean being Job stability and presenteeism (-0.131). These numbers suggest that cultural factors may have a greater influence on presenteeism than legal aspects of the employment contract.

The study of presenteeism in Brazilian electric power companies has identified manageable factors that influence it, hence factors that can be managed. The use of the Bootstrap method and the validation of results allowed the development of the Structural Model presented in Figure 2 and the correlations between first-order constructs after evaluating confidence intervals.

Figure 2

The model facilitates the understanding of the nuances behind presenteeism and shows the constructs that most influence its occurrence. It can also be seen that Personal Aspects are the most significant for the generation of presenteeism in electric power companies. Personal aspects refer to the individuality of the employee, so their particular situations and experiences can influence the occurrence of presenteeism. Furthermore, the results suggest that the manager-subordinate relationship may have a relevant influence on presenteeism and its consequences.

The cultural factors increasing presenteeism are represented by common observed behaviors. They are the second most representative item in the model. The impact of these behaviors on presenteeism points to the need for effective organization and monitoring by the manager to mitigate the occurrences of presenteeism. Koopman et al. (2002) highlighted the need for monitoring the volume and quality of work as an indicator of presenteeism. When the manager is distant or absent, presenteeist behavior can be seen as natural and permissible. The need for the manager to take on and fulfill their role in effective people management is evident. In addition, the Human Resources department, which supports managers in their role, can provide tools, review processes, and structure broader actions that have an impact on mitigating presenteeism occurrences.

Job stability appears as the third most significant item in the model for the occurrence of presenteeism. The results suggest the idea that stability creates a comfort zone and that the security generated in this context promotes presenteeism, assuming the absence of responsibility or consequences policies. Individualistic thinking and a lack of integration with the whole may relate to presenteeism justified by job stability. The understanding of the psychological contract established between the employee and the organization, as advocated by Rios and Gondim (2010), reaffirms itself as one aspect of the work relationship to be considered in identifying presenteeism. Additionally, it can be believed that a team-based results reward program can signal a policy of consequences and minimize the effects of presenteeism.

Gomes (2022) states that in many organizations there is a lack of knowledge and information about this correlation. Once the correlation between the studied factors and the occurrence of presenteeism is established, it becomes possible to take direct action in Human Resources Management, whether through workplace quality of life programs, leadership development, the establishment of consequence policies, or even cultural transformation enhancement projects.

The obtained results allowed achieving the objective of proposing a structural model based on the identification and measurement of factors influencing presenteeism, according to the perceptions of employees in companies in the electric power sector. The constructs that most influence presenteeism were Personal Aspects (α = 0.406), Cultural Factors increasing presenteeism (α = 0.399), and the perception of Job Stability (α = 0.388). Figure 1, associated with Table 1, provides managers with the necessary elements to establish priorities in actions aimed at reducing presenteeism.

Presenteeism is an undesirable event but is manageable. Presenteeism is paid work time that is not effectively utilized; it's unproductive time and can be understood as allowed sabotage. Its impacts on productivity are noticeable but often challenging to measure or quantify due to the difficulty in assessing its occurrences. The intangibility of presenteeism makes it challenging for this phenomenon to be included on the Human Resources agenda and to be addressed through various approaches. There is no doubt that managing presenteeism can bring benefits to both the company and its employees, leading to a win-win situation with positive outcomes for quality of life, satisfaction, productivity, and competitiveness in the market.

The Brazilian electrical sector, facing numerous challenges, requires professionals who are present and productive. Therefore, understanding and addressing presenteeism in electrical utility companies is a way to generate efficiency and productivity gains for the sector.

The mere acknowledgment that presenteeism is an event that can occur and can be influenced makes it a manageable event. The formulation of a structural model resulting from factors that influence presenteeism occurrences is a significant step in understanding and explaining such occurrences. It represents a differentiated perspective on the phenomenon for academia and provides food for thought for management.

The unique questionnaire used in this research, developed based on the international metrics WLQ-8 and SPS-S-6 (Ferreira et al., 2010), and the qualitative research conducted with employees from one of the companies, allowed for a close and comprehensible approach to presenteeism. Therefore, as a future research suggestion, it is recommended that the research instruments, interview guides, and questionnaires, be applied in different contexts and at different times, especially considering that the pandemic period (Covid19) brought significant impacts to organizations and consequently to work relationships. However, it is understood that this is a first step towards the development and consolidation of an instrument suitable for the Brazilian reality.

In conclusion, it is suggested that future studies explore the relationship between presenteeism and culture. It is also important to compare how these factors operate in the contexts of public, private, nonprofit organizations, and volunteer work specifically. Further research is recommended to better understand the influence of these factors on presenteeism in different organizational settings.

FAPEMIG e ANEEL.

Aguiar, G. A., & Burgardt, B. F. (2018). A presença ausente: reflexões sobre o presenteísmo nas organizações de serviço público. DESAFIOS-Revista Interdisciplinar da Universidade Federal do Tocantins, 5(3), 79-84. Recuperado de: https://sistemas.uft.edu.br/periodicos/index.php/desafios/article/view/4929

Aneel. (2015). Revisão Tarifária Periódica das Concessionárias de Distribuição: Submódulo 2.5 - Fator X. Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica. Recuperado de http://www2.aneel.gov.br/cedoc/aren2015660_Proret_Submod_2_5_V2.pdf .

Aronsson, G., & Lindh, T. (2004). Långtidsfriskas arbetsvillkor: En populationsstudie (Work conditions among workers with good longterm health: A population study). Work and Health 2004, 10.

Bardin, L. (2009). Análise de Conteúdo. Lisboa, Portugal.

Biron, C., Brun, J-P., Ivers, H. & Cooper, C. (2006). At work but ill: psychosocial work environment and well-being determinants of presenteeism propensity. Journal of Public Mental Health, December, 5(4), p. 26-37.. Recuperado de: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/17465729200600029/full/html

Bollen, K. A. (1989) Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Cancelliere, C., Cassidy, J. D., Ammendolia, C., & Côté, P. (2011). Are workplace health promotion programs effective at improving presenteeism in workers? A systematic review and best evidence synthesis of the literature. BMC public health, 11(1), 1-11. Recuperado de: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-395

Cenfetelli, R. T., & Bassellier, G. (2009). Interpretation of formative measurement in information systems research. MIS quarterly, 689-707. Recuperado de: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20650323

Chin, W. W. (1998). Issues and opinion on structural equation modelling. Management Information Systems quarterly, 22(1), 1-8.

Cooper, C. (2011). Presenteeism is more costly than absenteeism. HR Magazine, Strategic HR. p. 1. Recuperado de: https://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/content/features/presenteeism-is-more-costly-than-absenteeism /

Dutra, D., de Campos, M., Carneiro, A., & Junior, V. (2018) Gestão de pessoas e sua relação com a produção: um estudo de caso nas indústrias moveleiras do município de Pompéu/MG. Pesquisa & Educação a Distância, América do Norte. Recuperado de: http://revista.universo.edu.br/index.php?journal=2013EAD1&page=article&op=viewArticle&path%5B%5D=6556

Efron, B., & Tibshirani, R. J. (1993) An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman & Hall.

Elkeles, T., & Seligmann-Silva, E. (2010) Trajetórias recentes dos distúrbios osteomusculares em dois contextos nacionais: Brasil e Alemanha. In D. Glina, & L. Rocha (Orgs). Saúde mental no trabalho, 1a ed., Cap. 15.p. 302-334. São Paulo: Roca, 2010.

Fernandes, G. (2015) Estabilidade no Direito do Trabalho. Fonte: Jus Brasil. Recuperado de: http://guilhermefernandes1993.jusbrasil.com.br/artigos

Fernandino, J. A., & Oliveira, J. L. (2010). Arquiteturas organizacionais para a área de P&D em empresas do setor elétrico brasileiro. Revista de Administração Contemporânea - RAC, 14(6),p. 1073-1093. Recuperado de: https://www.scielo.br/j/rac/a/vhKZpmsxYwcBtjyFL9VtKKn /

Ferreira, A. I., Martinez, L. F., Souza, L. M., & Cunha, J. V. (2010). Tradução e validação para a língua portuguesa das escalas de presenteísmo WLQ-8 E SPS-6. Avaliação Psicológica. 9(2),p. 253-266. Recuperado de: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3350/335027283010.pdf

Flores-sandí, G. (2006) Presentismo: potencialidad em accidentes de salud. Acta MédicaCostarricense - AMC., 48(1), p. 30-34. Recuperado de: https://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?pid=S0001-60022006000100006&script=sci_arttext

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journalof Marketing Research, 18(1),p. 39-50. Recuperado de: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/002224378101800104

Gomes, P. A. L. (2022). A relevância dos programas de apoio psicológico nas organizações.. Tese de Doutorado. Instituto Superior de Economia e Gestão.

Halbesleben, J. R., Whitman, M. V., & Crawford, W. S. (2014). A dialectical theory of the decision to go to work: bringing together absenteeism and presenteeism. Human Resource Management Review, 24(2), p. 177-192. Recuperado de: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1053482213000491?casa_token=ZyYNh2zd38cAAAAA:9udP9Ak3UY44De3_QuedmebAGqChDOomlpaT6ftzGH_1FsBa_5Z03tOdKUfbesI8zhKRRBHEX4GO

Haque, A. (2018) Mapping the relationship among strategic HRM, intent to quit and job satisfaction: a psychological perspective applied to Bangladeshi employees. International Journal of Business and Applied Social Science, 4(4), p. 27-39. Recuperado de: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3171368

Haque, A., Fernando, M., & Caputi, P. (2019). Perceived human resource management and presenteeism. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 11(2), p. 110-130.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2009). Análise Multivariada de Dados. Porto Alegre: Bookman

Hollander, M., & Wolfe, D. A. (1999). Nonparametric Statistical Methods. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1999.

Koopman, C., Pelletier, K. R., Murray, J. F., Sharda, C. E., Berger, M. L., Turpin, R. S., Hackleman, P., Gibson, P., Holmes, D. M., & Bendel, T. (2002). Stanford presenteeism scale: health status and employee productivity. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 44(1),p. 14-20. Recuperado de: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44995848

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396.

Mingoti, S. A. (2007). Análise de Dados Através de Métodos de Estatística Multivariada: uma abordagem aplicada. Belo Horizonte: UFMG.

Monecke, A., & Leisch, F. (2012). SemPLS: structural equation modeling using partial least squares. Journal of Statistical Software, 48 (3),p. 1-32. Recuperado de: https://ro.uow.edu.au/commpapers/3138/

Morgan, G. (1996). Imagens da Organização. São Paulo: Atlas.

Oliveira, L. B. D., Cavazotte, F. D. S. C. N., & Paciello, R. R. (2013). Antecedentes e consequências dos conflitos entre trabalho e família. Revista de administração contemporânea, 17, 418-437. Recuperado de: https://www.scielo.br/j/rac/a/nWTv5vVw3fPzX7jGn93xN9P /

Raîche, G., Walls, T. A., Magis, D., Riopel, M., & Blais, J. G. (2013). Non-graphical solutions for Cattell’s scree test methodology.European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 9(1), p.23-29. Recuperado de: https://econtent.hogrefe.com/doi/full/10.1027/1614-2241/a000051

Rios, M. C., & Gondim, S. M. G. (2010). Contrato psicológico de trabalho e a produção acadêmica no Brasil. Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho, 10(1), 23-36. Recuperado de: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?pid=S1984-66572010000100003&script=sci_arttext

Sanchez, G. (2013). PLS Path Modeling with R. Berkeley: Trowchez Editions.

Santi, D. B., Barbieri, A. R., & Cheade, M. D. F. M. (2018). Absenteísmo-doença no serviço público brasileiro: uma revisão integrativa da literatura. Revista Brasileira de Medicina do Trabalho, 16(1), 71-81. Recuperado de: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/biblio-882541

Schein, E. H. (1990) Organizational culture. The changing face and place of work. The American Psychologist, Feb, 45(2), p. 109-119.

Schultz, A. B., & Edington, D. W. (2007). Employee health and presenteeism: a systematic review. Journal of occupational rehabilitation, 17, 547-579. Recuperado de: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10926-007-9096-x

Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V. E., Chatelin, Y. M., & Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modeling. Computational statistics & data analysis, 48(1), 159-205. Recuperado de: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167947304000519?casa_token=V-8XEfXyaesAAAAA:rXE4rrtpmdhI73xQVqdXfG7jAKm5ojG2R9s5wL96AI1ALthXpidZgfFZFfhZPLVYpxouM2xlGb3Y

Appendix - Interview Script

Interview script developed based on the main global scales for measuring presenteeism: Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ-8) and Stanford Presenteeism Scale (SPS-6) (Ferreira et al., 2010).

Definition: Presenteeism refers to a behavior in which an employee is "physically present" during regular working hours but is not actively engaged in productive work during a specific period of functional time.

------------

[1] A public service concessionaire is a private company that receives from the government the exclusive right to operate and provide essential services to the population in a specific geographic area. In Brazil, private companies in the electrical energy sector receive concessions to generate and supply electricity to residences, businesses, and industries.